Critical Diary 2 - Media, Technology and Society

- Danielle Lowenna

- Jun 6, 2024

- 8 min read

In Week 7, we explored compulsion and how media consumption may be increasing in an unhealthy way. Kruger suggests that social media sites are ‘recreating the slot machine’ (2018) and encouraging patterns of compulsion in users, who spend time online even when it is not fulfilling them. The first step in combatting compulsion or addiction is often recognising that there is an issue. Our brief was to create a TikTok-style PSA about healthy media habits, aimed at high school students, and I chose to create a video which would ask users to reevaluate if they wanted to remain on the platform, with the intention of interrupting mindless scrolling.

The Social Dilemma (2020) documentary highlights that social media is designed to keep us on the platforms as ‘our attention is the product being sold to advertisers’. Often there is an element of guilt associated with prolonged social media use, yet users still return to try and seek gratification from the platforms, ‘drawn into “ludic loops” or repeated cycles of uncertainty, anticipation and feedback’ (Schull, cited in Kruger 2018).

The title of my video ‘Doomscroll got you down?’ encourages users to self-evaluate whether their current social media habits are draining their mental health. Slaughter (2020) defines doomscrolling as ‘persistently scrolling… with an obsessive focus on distressing, depressing, or otherwise negative information’ (cited in Sharma et al. 2022). This was especially prevalent during the pandemic, where social media was a key source of information and connection during prolonged lockdowns. However, doomscrolling is arguably becoming more normalised post-covid and even integrated into the design of social media platforms.

Alter highlights in his TED talk (2017) that ‘the way we consume media today is such that there are no stopping cues; the news feed just rolls on and everything’s bottomless’. He compares this to 20th century media which had inbuilt stopping cues: a newspaper has a final page, a book has chapters, a TV show is divided into episodes and a broadcast will end. These are all satisfactory points where a user can disengage from the media product.

By contrast, the ‘pull-to-refresh and infinite scrolling mechanism’ (Kruger 2018) is where users may get stuck in a ‘doomscroll’ and my video intends to act as an artificial stopping cue. Particularly for an audience of ‘digital natives’ (Prensky, cited in Bennet, 2012) who have grown up on these platforms, it may be difficult to regulate time on these apps. Hence the TikTok-style video appeals to this younger demographic by appearing on the familiar platform, as opposed to creating a poster for a school hallway which may be ignored or deemed irrelevant.

There is an irony in accounts using these platforms to share messages about disengaging from social media. For example, @close_ig_daily describe themselves as a ‘daily reminder to you for getting off Instagram’. They post memes or reels which blend into the user’s feed to capture their attention and then interrupt the video with a ‘stop scrolling’ disclaimer. Accounts like @stop_scrolling_ just post their logo as a reminder, lacking a trending audio or narrative which would be picked up by algorithms and prioritised on users’ feeds.

This was a key consideration in my video, as I aimed to use popular codes of communication in order to align with the platform enough to be promoted on feeds and reach the audience, whilst still ultimately persuading people to get offline.

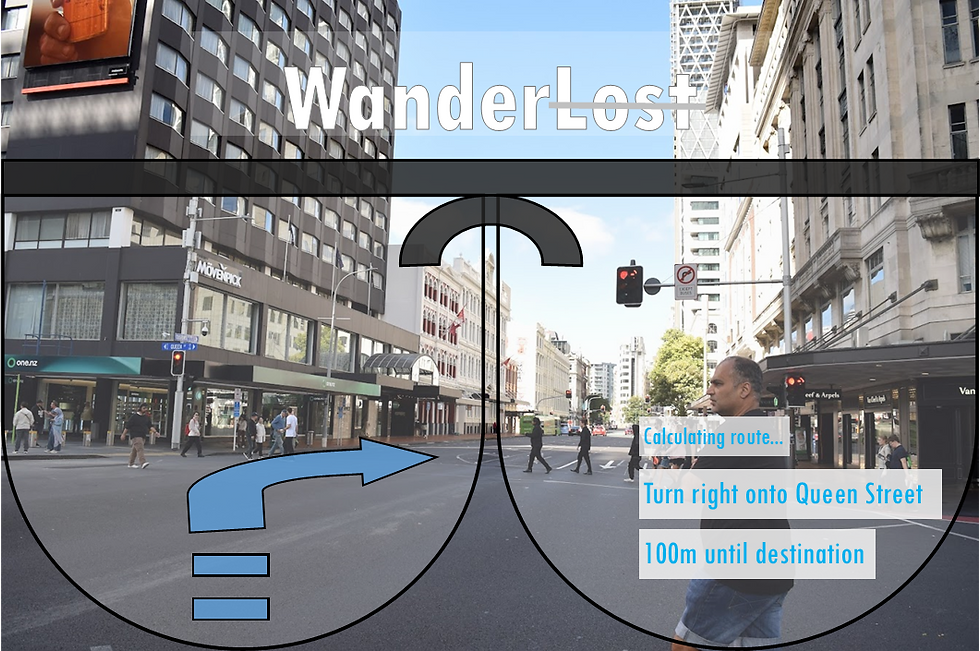

In Week 8, we explored how artificial intelligence (AI) could be used in our studies. I chose to focus on the application of AI in journalistic work, particularly the ethical issues associated with using chatbots such as Chat GPT.

Machine learning is a subset of AI, defined as having the ‘capacity to learn and improve its analyses through the use of computational algorithms’ (Matthew-Helm et al. 2020). AI is no longer sought out, instead now ‘fundamentally ingrained… and often functions invisibly in the background of our personal electronic devices’. For example, the Instagram search bar now says ‘ask Meta AI anything’. This means that AI is inevitably part of my studies, consciously or otherwise.

Researching can be simplified by using Chat GPT, however O’Neil (2016) highlights the risk of AI ‘deepening existing social inequalities by perpetuating biases found in training data’. In the context of journalism, Baeza-Yates (2018) found that ‘70% influential journalists in the US were men… algorithms learning from news articles are thus learning from articles with demonstrable and systemic gender bias’. This research then suggests that personalised algorithms exacerbate this further when factoring a user’s own ‘self-selection bias’. If a student is only shown sources within their existing framework of research, does this challenge them to develop their theories or explore criticisms?

‘It is important to remember that AI, despite its ability to generate new content, is only as smart as the data that it has read and processed before.’ (Frommherz and Sissons, 2023). Their research highlights that elements of Chat GPT’s responses were largely ‘superficial’ and unable to generate techniques ‘specific to the management of difficult, confusing, contentious, conflicting or otherwise complex communication events.’ Consequently, students should not rely on AI as an omniscient source of information, instead recognising the limitations inherent in the system.

Similarly to Chat GPT, journalism relies on taking complex events and disseminating these to the reader in everyday language. For example, reporting on a conflict could have multiple angles and layers of context to sift through. If a journalist relied on AI for a summary of events without knowing the nuances themselves, they would risk oversimplifying a contentious issue or presenting a biased story, simply through lack of context.

Amato et al. (2019) suggest that ‘trust and transparency of algorithms’ is a key challenge in integrating AI in the production and distribution of news. The use of Chat GPT to generate sentences or headlines for news articles could be argued to undermine an audience’s trust in a journalist’s work, as they are no longer hearing the writer’s voice, despite them claiming credit in the byline. This ownership dispute adds to my reluctance in using Chat GPT, as having to reverse-search AI content to verify and credit sources undermines its function as a time-saving tool.

Harari (2017) holds ‘faith in the development and enforcement of ethical AI frameworks’, suggesting that there is a ‘moral panic’ (Cohen, 2011) about the growth of AI. Similarly, Winston’s ‘law suppression of radical potential’ (1998) highlights that ‘constraints operate to slow the rate of diffusion so that the social fabric in general can absorb the new machine’, suggesting that AI would not be this prevalent if institutions, whether universities or newsrooms, were not equipped to deal with the technology and its implications.

Week Ten developed our research into surveillance, exploring ideas of the panopticon (Foucault, cited in Brunon-Ernst, 2012) and the ‘few watching the many’ in relation to policing and law enforcement.

Our brief was to create a counter-surveillance document which would aid a marginalised group, likely to receive higher scrutiny despite engaging in non-criminal activity. I chose to focus on the surveillance of protest groups, such as recent pro-Palestine marches in Auckland.

Figure 9: Video highlighting police presence patrolling alongside a Palestine protest. March 9th, Queen Street Auckland. Video: Danielle Hutchinson.

In New Zealand, the Bill of Rights Act 1990 entitles the public to protest peacefully as part of their right to freedom of expression. However, there is often a strong police presence at public demonstrations and, particularly in Europe, arrests are regularly made in response to climate protests. For example, high-profile activist Greta Thunberg has been detained on a number of occasions. This means that protesters, no matter their status, risk getting a criminal record, despite being legally entitled to protest. Hence, individuals who attend protests are arguably more likely to be labelled as ‘high-risk’ and subject to increased surveillance.

One of the key issues highlighted in my counter-surveillance document was that surveillance does not necessarily come exclusively from commercial buildings or official institutions, due to the phenomenon of ‘surveillance creep’ (Ball, Haggerty and Lyon, 2012). CCTV cameras and phone GPS tracking are both examples of how technology has moved beyond its initial scope and become more prevalent in society. For example, a crime centre in DC recently asked residents to link personal cameras to the police network. This highlights that surveillance does not just come from official infrastructure but is also on the rise in residential areas, popularised by products such as Ring doorbells.

As a journalist, I attend protests in order to report on events, which involves talking with participants and picking up flyers. Not only will my phone location place me at the protest, but social media livestreams and photos of the crowd may also show my attendance, despite having no political affiliation with the event. This raises the question of whether engaging with protests immediately profiles you as a protester. Ball, Haggerty and Lyon (2012) argue that the profiling techniques associated with surveillance result in ‘classifications [that] affect people’s choices and life chances’.

This links to a key element of my counter-surveillance document, which asks individuals to evaluate what they share on social media about attending protests. Zuboff highlights that we now have a trail of ‘digital breadcrumbs… your whole life will be searchable’ (2019). As a result, individuals should be mindful of what they make publicly available online.

There is an irony in that the purpose of protesting is to raise awareness of an issue, not hide the fact that you were attending. The concept of a counter-surveillance document suggests that the onus is on the individual to take precautions in protecting their privacy. However, it could be argued that institutions facilitating surveillance should also be more transparent about how they use the public’s data.

The police are under growing scrutiny about how they engage with protests. Last month in the UK, the High Court found the Home Office ‘unlawfully put peaceful protesters at… unfair risk of prosecution’. Part of my counter-surveillance document would be an overview of current laws, such as the legal extent of surveillance, institutions’ use of data, and your rights as a protester.

Although this document may decrease vulnerability to systematic surveillance, it could be seen to simply shift the pressure to ‘self-surveillance’ (Bartky, cited in Kanai 2015) through increased image maintenance.

References

Alter. (2017, August 2). Why our screens make us less happy [TED talk]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0K5OO2ybueM

Amato et al. (2019). 2.4.3 News. AI in the media and creative industries, 28-29.

Baeza-Yates. (2018). Bias on the web. Communications of the ACM, 61 (6), 54-61.

Ball, Haggerty and Lyon. (2012). Routledge handbook of surveillance studies. Routledge.

Bartky, cited in Kanai. (2015). Thinking beyond the internet as a tool: Girls’ online spaces as postfeminist structures of surveillance. In Bailey and Steeves (Eds.), eGirls, eCitizens: Putting Technology, Theory and Policy into Dialogue with Girls’ and Young Women’s Voices (pp. 83 – 106). University of Ottawa Press.

Cohen. (2011). Folk devils and moral panics. Routledge.

Foucault. (1975). cited in Brunon-Ernst. (2012). Beyond Foucault: New Perspectives on Bentham's Panopticon. Taylor & Francis Group.

Frommherz and Sissons. (2023). Why we need complexity: A conversation with AI. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, 12, 277-297.

Harari. (2017). Homo Deus: a brief history of tomorrow. Harper.

Kruger. (2018, May 8). Social media copies gambling methods 'to create psychological cravings'. Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan. https://ihpi.umich.edu/news/social-media-copies-gambling-methods-create-psychological-cravings

Matthew-Helm et al. (2020). Machine learning and artificial intelligence: Definitions, applications, and future directions. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 13, 69-76.

O’Neil and Gunn. (2016). Near-term artificial intelligence and the ethical matrix. In Matthew Liao (Ed.), Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Oxford University Press.

Orlowski. (2020). The social dilemma [Documentary]. Netflix, access via Auckland University of Technology. https://aut.au.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=9236beaf-b4e9-424d-9887-afe700157da0

Prensky. (2001). cited in Bennet, (2012). Digital Natives. In Yan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cyber Behaviour. IGI Global.

Schull, cited in Kruger (2018, May 8). Social media copies gambling methods 'to create psychological cravings'. Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan. https://ihpi.umich.edu/news/social-media-copies-gambling-methods-create-psychological-cravings

Slaughter. (2020). cited in Sharma et al. (2022). The Dark at the End of the Tunnel: Doomscrolling on Social Media Newsfeeds. Special collection: Technology in a time of social distancing. Technology, Mind, and Behaviour, 1-13.

Winston. (1998). Media, Technology and Society: A History: from the Telegraph to the Internet. Routledge.

Zuboff. (2019). Surveillance capitalism and the challenge of collective action. New Labor Forum, 28 (1), 11 – 29.

Comments