Critical Diary 1 - Media, Technology and Society

- Danielle Lowenna

- Apr 10, 2024

- 5 min read

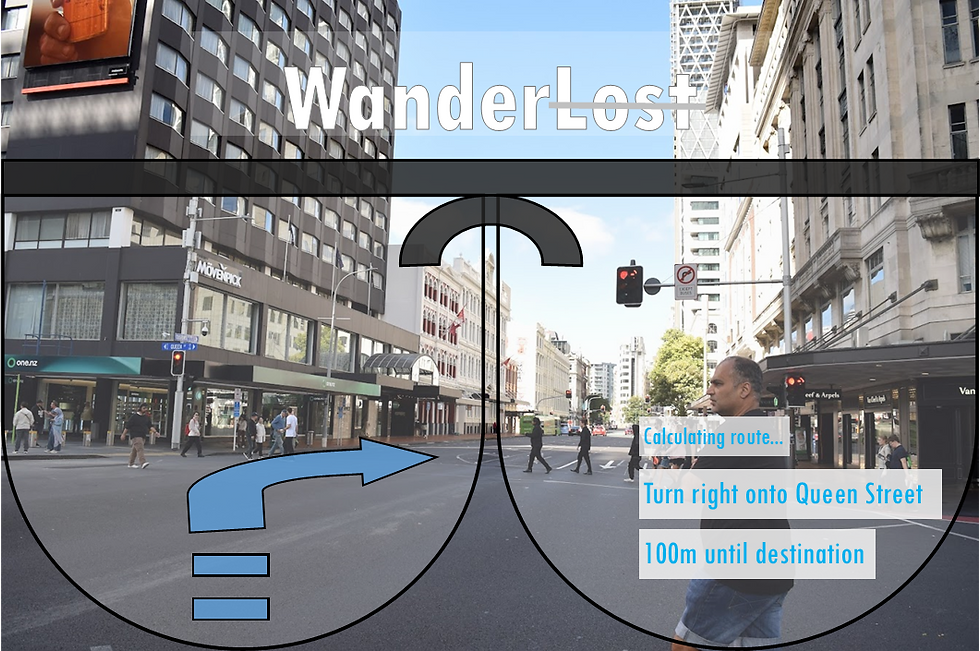

Our brief in Week Two was to create a new media device which fulfils a need in modern Aotearoa, whilst incorporating the latest advances in technology. McLuhan defines technology as a ‘direct extensions of the human body or senses’ (2008) and our device is an extension of the sense of sight. Using augmented reality (AR) we conceived a pair of ‘WanderLost’ travel glasses which could virtually ‘project’ map directions onto the street in the user’s field of vision. The user would then be less susceptible to being victims of crime as they can navigate a new location discreetly without walking around with a map or similar indicator of being lost. This would be especially useful for solo female travellers or other vulnerable individuals who are at risk of being targeted.

Furthermore, the glasses would have the option to overlay language translations of street signs onto the user’s visual display and translate real-time conversations. This would allow the user to seamlessly integrate into a new country and communicate in everyday interactions, such as buying something in a store or asking for advice.

The success of this idea would rely on the progression from a prototype to invention, which Winston argues is down to social forces whereby ‘a supervening necessity has created a partial need which the prototype partially fills’ (1998). In our case, there is a growing need for intercultural communication in daily life. This can be seen in cities such as Auckland, with expanding multicultural communities due to globalisation and migration. Furthermore, since lockdown restrictions have lifted, there is an increase in international travel and growing numbers of people navigating foreign countries – whether that’s international visitors arriving in Aotearoa or New Zealand nationals travelling abroad.

Applying Braudel’s concepts of ‘brakes and accelerators’ (cited in Winston, 1998), this supervening necessity would act as an ‘accelerator’ and enable the prototype to develop into an invention. Our device would be unlikely to be affected by the ‘suppression of radical potential’ as over the past decade VR and AR has become more commercially viable and accepted into household markets. Therefore, there is little need for a ‘brake’ so that ‘social fabric can absorb the new machine’, as the technology is already growing in popularity and is permitted by existing regulatory structures.

One of the main risks to our idea is the overlap in technology currently provided by Google, such as Google Lens, Google Maps, or Google Translate. We would have to differentiate our technology and develop our software enough to have our own patent, which is unlikely to be commercially viable for a start-up with limited time and resources. Alternatively, we could sell the rights to Google and merge with the conglomerate to bring the invention to their market of existing consumers, rather than being a commercial competitor.

Our following brief, in Week 5, was to develop an app to aid the revitalisation of the Māori language. This aligns with Mahuta’s research which suggests that ‘in order to survive, endangered languages must begin to inhabit traditionally English dominated spaces, particularly digital spaces’ (2017).

Kupu is an example of an existing Māori language app which begins to inhibit these digital spaces. It enables users to scan everyday items and see the Māori translation, pronunciation and similar words. It had a positive uptake when initially launched in 2018, yet since then downloads have tailed off. This may be due to the basic functionality of the app which is useful as a casual dictionary, but lacks features to encourage daily engagement or repeated use. This is important when competing for attention with other apps, such as social media, which give regular notifications and entice users back to their content.

Our app would focus on competition and leaderboards, modelling the style which has made Duolingo the number one language-learning app in the world, with 24.1 million daily active users in 2023. Being able to connect with friends and challenge other players across the world reinforces a sense of community and repurposes elements of social media ‘to build a digital house’ (Mahuta, 2017) for Māori speakers to convene.

Seeing as Kupu is Māori for ‘speak’, our app would be called Kōrero ‘discussion’, as the aim is not just for a person to speak alone, but to share their language-learning journey with others. This reflects the importance of ‘sustaining virtual language communities to aid in the revitalisation efforts of Indigenous language groups who are struggling to sustain physical language communities’ highlighted by Mahuta. An app with a global leaderboard would connect the diasporic speakers of Māori, regardless of their physical location, strengthening the digital network of the community.

When creating the app, the Tāmata Toiere database would be a valuable source of information. The digital archive was created to document the language and prevent further losses of waiata and haka due to the passing of elders, a phenomenon highlighted by Moorfield (2006: cited in Ka’ai-Mahuta 2012). Whilst the archive is comprehensive, it lacks the modern interactivity which would engage with younger generations. There is a cultural necessity of preserving the Māori language, but our ‘supervening social necessity’ (Winston, 1998) is to engage with younger audiences, as without interest in the language, these archives are at risk of simply collecting dust and being similarly forgotten.

Our app would allow users to unlock new levels, vocabulary and bonus audio-visual content, varying the format of language-learning. A daily quiz or ‘on this day in Māori history’ segment would appear as notifications to encourage regular engagement with the app, gratifying users with new content.

However, it would be difficult to rival Duolingo’s established language-learning platform. There could be a potential to collaborate with the company to create a Māori course, as Duolingo have gained success with their Welsh and Gaelic courses, which have reached 3 million and 1.8 million users respectively as of the end of last year. This shows that they have an established consumer base interested in the revival of indigenous languages and that a similar app teaching Māori could be highly effective.

As Ka’ai-Mahuta points out ‘it is very apparent that Māori embraced new opportunities, such as literacy and the recording mechanisms, to ensure cultural continuity’ so it stands to reason that perhaps a new interactive app is the next step on this journey of cultural preservation to endure the 21st century.

References

Braudel, F. cited in Winston, B. (1998). Introduction: A storm from paradise. Technological innovation, diffusion and suppression. Media, technology and society: A history: from the telegraph to the internet. pp. 1-18. Routledge.

Ka’ai-Mahuta, R. (2012). Digital technology: Contemporary methods for the dissemination of ancient knowledge. The use of digital technology in the preservation of Maori song. Te Kaharoa, 5(1), pp. 99-108. Te Ara Poutama.

Mahuta, D. (2017). Building virtual language communities through social media – because we don’t live the village life anymore. In Whaanga et al. (Ed.) He Whare Hangarau Māori: Language, culture & technology. pp. 42-45. Te Pua Wānanga ki te Ao / Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies.

McLuhan, M. (2008). The medium is the message. In Mortensen, D. (Ed.) Communication theory, second edition. Routledge.

Moorfield (2006) cited in Ka’ai-Mahuta, R. (2012). Digital technology: Contemporary methods for the dissemination of ancient knowledge. The use of digital technology in the preservation of Maori song. Te Kaharoa, 5(1), pp. 99-108. Te Ara Poutama.

Winston, B. (1998). Introduction: A storm from paradise. Technological innovation, diffusion and suppression. Media, technology and society: A history: from the telegraph to the internet. pp. 1-18. Routledge.

Comments